- Home

- Michael Griffo

Moonglow Page 20

Moonglow Read online

Page 20

“Yeah,” he says as if his comment made sense. “ ’Cause you’re half Little Red Riding Hood and half the Big Bad Wolf. Operation Big Red.”

Makes a lot of sense actually. But where was I? “I don’t care if Nadine’s a part of . . .”

“Operation Big Red.” Archie finishes my sentence and the snowman cookie simultaneously.

“Yeah, that,” I say. “I don’t trust her.”

Sitting on the bar stool at my kitchen counter, Archie swivels from left to right. In the middle of the return trip, he stops himself only long enough to look at me and ask, “Why not, Domino?”

“Because of what she said,” I say.

Another swivel to the right and back again. “What did she say?”

This time when he’s facing me, I reach across the kitchen counter and grab his wrist. I get a flashback of when I grabbed Jess, when I was so close to breaking her wrist. Ashamed, I let go of Archie so he can keep swiveling and hope that he doesn’t realize what memory was just floating through my mind. Since he just popped a whole snowflake in his mouth, I’m guessing he doesn’t.

Chewing, Archie asks, “Are you having second thoughts about confiding in her yesterday?”

Sitting on the stool next to Archie, I turn him so he’s facing me. “Yes,” I reply. “But only because I think she’s hiding something.”

“Maybe it’s just that you’d rather be, you know, a lone wolf?”

“Archie!” I shout, slapping him on the shoulder.

“Sorry, Dom,” he says, laughing. “I’m still not convinced that this curse thing is legit. I mean it’s fun in a bizarre ‘you might be suffering from post-traumatic stress’ sort of way, but I just don’t see you as the wolf type. Perhaps a peacock—you do pride yourself on looking pretty.”

I used to also pride myself on my conviction. Once I made a decision, I stuck with it; I didn’t flip-flop like some shifty politician. But my opinion of Nadine is constantly changing. I think she’s freakish; I think she’s cool. I think she’s my soul mate; I think she’s my enemy. I don’t know what to think about her. So I’ll let Archie decide for me.

“What did I tell you about the woman who put the curse on my father?” I ask.

“That she saw her husband get shot, she was pregnant, and she put a curse on your father’s head,” he recaps.

Good, just what I thought. But I need to be sure before I continue. “What tribe was she from?”

“Tribe?”

“Was it the Arapaho?”

“Oh! Pregnant curse lady was a Native American Indian!” Archie exclaims. “You never mentioned that.”

Perfect! “Then how do you explain what Nadine said before she left?” I ask. “She referred to the pregnant woman as an Indian.”

“She did?”

“Yes!” I scream. “Right before you both left, she said something like, ‘In three days we’ll find out if this Indian woman’s curse really has any power and if it really will come true.’ I heard it.”

“I didn’t,” he replies.

Not so perfect! “What do you mean you didn’t hear it?”

“Just what I said,” he replies, reaching for a gingerbread man. “I didn’t hear her say that.”

“Well, she did,” I confirm. “And how could she possibly know that the woman who cursed my father was an Indian if I didn’t mention it?”

“Well, c’mon, Dom, what else could the woman be?” he asks, biting off a gingerbread leg. “Think about it. We’re surrounded by reservations; Indians are superstitious people. Nadine is smart; she put two and two together and came up with four.”

More logic. Quickly followed by speculation.

“But are you sure you didn’t mentally slip the word into her sentence yourself ’cause you want a reason not to like Nadine?” Archie asks.

I’m shocked. Not because Archie is off the mark, but because he may have hit a bull’s-eye.

“Archibald Angevene, why would you say something like that?”

“Because, Dom, I wouldn’t call you a mean girl,” Archie says. “But you are pretty and popular and pert.”

“Pert?”

“I needed another p word, and that’s all I could think of.”

“Will you be serious?” I ask. “Do you really think I’m looking for a reason not to like Nadine?”

Before Archie can contemplate reaching for another cookie, I shut the lid on the container. No more distractions, just answers.

“It’s possible,” he hedges. “I mean, she’s an outsider, she’s super smart, and she’s closer to the ‘before’ pictures in a ‘before and after’ makeover photo spread, and, let’s face it, that’s kind of icky to a girlie girl like you.”

Can Archie really think I’m that superficial?

“Plus there’s the whole Napoleon thing,” he adds.

Nope. He was just leading up to the more substantive material.

“We all know Jess loved Nap; Nap’s into you instead,” Archie spells out. “So you’re protecting Jess by not liking Nap and by extension not liking—or not trusting—his twin, Nadine.”

Hmm. Napoleon does annoy me, especially after he told me that he had to be convinced to go to Jess’s funeral, so maybe I’m displacing my dislike for Napoleon onto Nadine because I don’t want to give Napoleon the satisfaction of knowing that he irks me. Kind of complicated, yet straightforward at the same time.

“You’re right. Nadine must’ve drawn her own conclusion about Luba’s ethnicity. How else could she know anything about this crazy woman?” I decide. “Who, by the way, I’ve dubbed Psycho Squaw.”

“Holla!” Archie beams. “Love the label even though it’s très politically incorrect.”

“I don’t mean to be offensive or, you know, malign an entire race or anything,” I protest. “Just denounce one mentally unstable woman.”

“And from what I’ve heard about this Luba woman, your nickname is spot on,” Archie says. “So anyway, it looks like Nadine made a lucky guess, end of story. Can we now exchange Christmas gifts?”

Archie pulls my gift out of his bag and places it on the counter. The wrapping is as swanky and nontraditional as I’ve come to expect from him. Fuchsia metallic paper and a hot pink bow that looks quite expensive. The gift does not.

“Wow, Arch, um, this is . . . nice,” I stutter. “I mean what girl wouldn’t want a notebook for Christmas.”

Shaking his head and tsk-tsking rapidly, Archie smiles. “I knew you’d think that!” he chastises. “It’s not a notebook.”

I pick up the notebook and open it so the blank pages are staring Archie in the face.

“It’s filled with lined paper, and it’s got a spiral binding,” I tell him. “It’s a notebook.”

“No,” he insists. “It’s a journal.” Semantically different, but literally the same thing.

“With all the, you know, issues you’ve been having lately, what with Jess’s death and this curse thing,” he whispers, “I thought you could use a journal to write down all your feelings so they don’t, you know, overwhelm you.”

A cheap gift, but a thoughtful one. And practical. I have been bombarded by thoughts and feelings and emotions lately, ranging from anxious to hopeful to despondent, and until I have some real answers maybe the best thing to do is to write down how I’m feeling, sort through all the confusion with a pencil as armor. This $1.99 gift may be my salvation.

“Thank you, Archie,” I say, my voice catching unexpectedly with gratitude. “It’s perfect.”

The combination of my words and my tone makes Archie blush. He’s silent for a moment as he searches for the right way to respond.

“Now where’s my gift?” he asks.

Excellent! Sentiment is useful, but only when underused.

Archie’s present is tucked underneath our tree, so we move into the living room so I can retrieve it. I have to kneel on the floor and rearrange some other gifts to find it, and suddenly I’m hit with one of those powerful emotions: guilt. It seems so w

rong that we should be celebrating, that we should be doing anything except mourning Jess. This should not be a house of cheer; it should be a house of remorse.

When I stand up I lose my balance and teeter a bit to the side before bracing myself by grabbing the arm of the couch. Archie’s not concerned; he probably thought I was stepping out of the way so I didn’t step on the ornament I dislodged from a branch when I grabbed his gift. The ornament that also happens to be my mother’s favorite.

A gold satin ball with its insides scooped out to hold a family photograph. I bend down to pick it up, and the joy wafting off the photo cuts right through me; I can feel how happy we used to be, all four of us, so long ago. Tracing a finger along the black velvet bow on top of the ornament, I remember my mother saying that as long as you have happy memories, you can have a happy life. It’s the first time I think my mother was wrong about something.

“I’m waiting!”

Standing behind me, Archie’s got his hands on his hips, only half-serious, and I don’t blame him. He deserves some Christmas cheer even if I’m not fully convinced I’m worthy of it.

Flopping on the coach, Archie rips the gift out of my hands and proceeds to rip off the wrapping paper. Of course this is when I get second thoughts that it was a totally stupid idea. Up until now I thought it was brilliant. In fact, I picked it out in September, and I’ve been holding it ever since. Too late now to find something else.

“A key?” Archie asks. “To what?”

I hold up the brass key, about twelve sizes larger than normal, and tell Archie that it’s the key to the town of Weeping Water. As sheriff, my father gives them out to outstanding citizens, those who have exhibited bravery or charity or creativity; I’m giving it to Archie to remind him that he possesses all three.

“It’s so you’ll always know that you have a home and that you belong here,” I say.

Archie’s mouth opens, but no words fall out. I follow his lead and don’t try to fill the silence; I give him whatever time he needs. Finally, after about a minute he knows what he wants to say. It’s not what I expect.

“Right before junior high I almost ran away,” he admits.

I had no idea. “Why?”

He tilts his head to the side and smiles. “Think back. Do you really have to ask?”

Archie is incredibly self-assured and well liked for an out-of-the-closet albino, but thinking back I do remember a time when he was considered by a huge number of our classmates to be nothing more than the freaky-looking gay kid. He’s become so much more confident since we first became friends in grammar school, I forget about that unhappy part of his past.

“I’m sorry, Archie. I’m shocked,” I reply honestly. “What made you change your mind and stay?”

“The day before I was going to run you invited me to your end-of-summer Labor Day party,” he says. “It reminded me that I had friends and I wasn’t alone.”

“Well . . . I’m glad I got you to change your mind,” I say, trying unsuccessfully not to cry.

Holding up the key, Archie replies, “After that invite this is the nicest gift anyone’s ever given me.”

Our hug is everything a hug between friends should be, easy, comforting, and safe; it’s nothing like the hug my father gives me later on when he comes home. His is awkward, rushed, and disturbing. Almost as disturbing as how easy it is for him to lie.

“I’m not lying for your sister, Barnaby,” I overhear my father say. “I’m protecting her.”

One inch closer and I’m at the edge of the living room. They’re both sitting on the floor surrounded by a crinkled sea of ripped wrapping paper, the result of opening up some Christmas gifts early. My father’s back is to me, and, if Barnaby were looking straight ahead instead of at the floor and the new electronic gadget, PS 20 something or other, he just got from Santa, he would see me. But he’s too upset and confused to make eye contact with anyone.

My father’s voice is gentle and firm, and still Barnaby doesn’t meet his gaze. “I’ve already questioned Dominy, like I would question any potential witness,” he says. “But she can’t remember anything about that night. It’s a blank.”

My father brushes away my brother’s bangs with his fingers, and their resemblance intensifies. I remember seeing photos of my dad when he was a kid, and Barnaby looks just like him. Same brown hair, same blue eyes, same wrinkled forehead. Now there are so many wrinkles on his forehead it looks like it might explode.

“But she already confessed to killing Jess!” my brother shouts.

“Of course she did,” my father answers in an eerily calm voice. “Because that’s the only thing that made sense to her at the time.”

The wrinkles slowly disappear, and I can tell that Barnaby is trying to accept what my father just told him. As much as he sometimes hates me and as frustrated and scared as he is right now, he doesn’t want to believe that his big sister’s capable of killing someone.

“Then what happened out there?” Barnaby asks.

I see my father grab Barnaby’s hands and hold them tight; they look so small next to my father’s. “We just don’t know, Barnaby,” he lies.

Fighting the urge to cover up the nativity scene under the tree to protect the residents of that holy barn from such blasphemy, I retreat into the kitchen. My father was so convincing I almost believed him. Sadly I realize that since he’s been lying since he was my age; he’s become a master. Not only a master at lying, but at upholding tradition as well.

My father never wanted us to spend Christmas at a nursing home—and I’m sure my mother would second that decision—so we always visit her on Christmas Eve. An hour later that’s where we find ourselves. And as I’ve said The Retreat is a first-rate facility, a go-to stop for those who need rehabilitation of the body and the mind; but it is what it is, and what it isn’t, is a happy place to be on a holiday. By the look on Essie’s face, she shares my opinion.

The bulk of the holiday decorating budget seems to have crash-landed on her desk, which makes for a particularly frightful sight. Sloping strands of braided garland in neon red and green hang from the edges of her desk, which itself is covered in a layer of fluffy cotton in an attempt to create a snowy panorama. Amid the puffs of cotton are lopsided trees, dancing elves, forest critters, snowmen and their snow families, and an endless variety of reindeer. Obviously Essie isn’t a member of PETA. The deer make me think of my father, so when I see a few toppled over, half-hidden in the cotton drifts, I don’t think that they’re simply exhausted from too much holiday cheer and resting; I presume they’ve become some teenage hunter’s bounty. Such happy thoughts fill my head. Where the hell are the sugar plum fairies this year?

The wall behind Essie’s desk has been turned into a giant present. It’s covered in red construction paper, with two lines of black masking tape, one horizontal and one vertical, and a green bow stuck on at the point where the lines intersect. But the most miserable-looking decoration is Essie herself.

Sitting at her desk Essie is wearing a Santa hat and a green sweater that depicts a gingerbread family all holding hands, frolicking in a winter wonderland underneath a star-filled night sky. The largest star actually twinkles, so I can only assume she’s stuck a battery in her bra. The problem is Essie looks like she was held at gunpoint when she got dressed to come to work.

“Hi, Essie,” my father says. “Merry Christmas.”

“Will be when my shift’s over,” she replies.

The three of us can’t help but laugh at Essie’s comment, but she isn’t looking for any positive reinforcement. When she hands us our index cards, she looks especially surly, or perhaps it’s just the contrast between her sourpuss face and the card’s holiday redesign. Tonight’s index card has been cut into the shape of a snowflake, and the one is written in green sparkly marker, the nine in red. There isn’t a Christmas bonus large enough to make Essie do any extra work, so I’m guessing Nadine and her fellow volunteers spent hours cutting index cards into holiday shapes.<

br />

Entering my mother’s room is like entering a monk’s hideout after spending time in the Vatican. The only decoration on display sits on the windowsill. It’s the angel that used to perch on top of our tree when my mom was alive. Well, really alive. Like my mother, the angel has blond hair; unlike my mother she’s wearing a red sequined gown.

During our brief visit, my father and I take turns holding my mother’s hand while Barnaby remains seated the entire time. He’s never touched my mother, not once in the whole time she’s been at The Retreat. He was only four when she was brought here, so his memories of her are dim and beyond his reach; to him our mother is really just a woman in a bed, nothing more. There’s little connection between them, and I’m sure today’s mandatory visit is a nuisance to him, not a selfless and necessary activity. Funny, I’m only two years older than Barnaby, and yet I remember my mother vividly. Honestly, I’m not sure what’s worse: to be like me and miss her terribly or be like Barnaby and not remember her at all.

Less than thirty minutes later we leave. Essie is the most animated I’ve ever seen her in my life, I’m guessing thanks to the rum-smelling eggnog she’s drinking. In between sips she hums along to some guy over the loudspeaker who’s singing a very melancholy version of “White Christmas.” His voice is deep and sad, as if he were trying to burrow a hole into the ground with his notes so he could hide from the holiday.

“I miss Bing, don’t you?” Essie asks.

Barnaby and I look at her with blank faces.

“Bing Crosby,” my father mutters to us. Then he responds politely to Essie. “He sure did have a beautiful voice.”

His voice could only be considered beautiful if you want to spend the Christmas holiday with the dying. And then I get a fit of the gigglaughs so uncontrollable I can’t stop, not after Barnaby shoots me a dirty look, not after Essie and my father stare at me sternly, trying to telepathically remind me that such an outburst of laughter is inappropriate. But it’s incredibly appropriate; they just don’t get it.

Since my life may be over in two more days, I understand that Bing in his deadly serious voice is singing his sad, pathetic song just for me.

Unwelcome aa-2

Unwelcome aa-2 Moonglow

Moonglow Unafraid aa-3

Unafraid aa-3 Sunblind

Sunblind Starfall

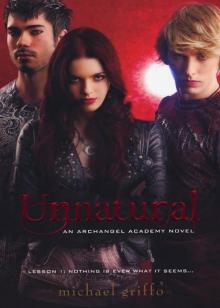

Starfall Unnatural

Unnatural Unafraid

Unafraid Unwelcome

Unwelcome Unnatural aa-1

Unnatural aa-1