- Home

- Michael Griffo

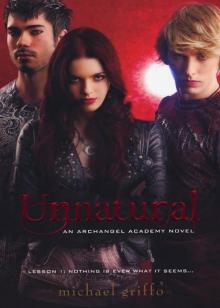

Unnatural aa-1

Unnatural aa-1 Read online

Unnatural

( Archangel Academy - 1 )

Michael Griffo

Michael Howard and Ronan Glynn-Rowley meet at Archangel Academy, an all-boys school in Eden, a rural town in north western England. Both are outcasts and decried as unnatural, Michael because he's gay, and Ronan because he's a hybrid vampire.

Unnatural

Archangel Academy - 1

by

Michael Griffo

Acknowledgments

I’m enormously grateful to my agent, Evan Marshall, for his support, honesty, and willingness to take a chance on an unknown writer. I am equally indebted to my editor, John Scognamiglio, for his insight, vision, and enthusiastic encouragement. I can’t imagine my work or my career being in better hands.

And special thanks to Linda, Lori, Jim, and Joan for giving me a quiet place to write when I couldn’t find some quiet on my own.

one drop

two drops

three drops

four floodgates open

the waters pour cool and

warm and

clear and

red am I alive?

or am I dead?

prologue

Outside, the earth was wet.

The rain had finally stopped, but it had poured hard and long during the night, the sudden storm catching the land unprepared for such a prolonged onslaught. From Michael’s bedroom window he could see the dirt road that led up to his house had flooded and the passageway that could lead him to another place, any place away from here, was broken, unusable. Today would not be the day he would be set free.

Ever since Michael was old enough to understand there was a world outside of his home, his school, his entire town, he had fantasized about leaving it all behind. Setting foot on the dirt path that began a few inches below his front steps and walking, walking, walking until the dirt road brought him somewhere else, somewhere that for him was better. He didn’t know where that place was, he didn’t know what it looked like; he only knew, he felt, that it existed.

Or was it all just foolish hope? Peering down from his second-floor window at the rain-drenched earth below, at the muddy river separating his home from everything else, he wondered if he was wrong. Was his dream of escape just that, a dream and nothing more? Would this be his view for all time? A harsh, unaccepting land that, despite living here for thirteen of his sixteen years, made him feel like an intruder. Leave! He could hear the wind command, This place is not for you. But go where?

On the front lawn he saw a meadowlark, smaller than typical but still robust-looking, drink from the weather-beaten birdbath that overflowed with fresh rainwater. Drinking, drinking, drinking as if its thirst could not be quenched. It stopped and surveyed the area, singing its familiar melodious tune, da-da-DAH-da, da-da-da, and pausing only when it caught Michael’s stare. Switch places with me, Michael thought. Let me rest on the brink of another flight, and you sit here and wait.

And where would you go? the meadowlark asked. You know nothing of the world beyond this dirt.

Nothing now, but I’m willing to learn. The lark blinked, its yellow feathers bristling slightly, but I’m not willing to forget everything that I know. Da-da-DAH-da, da-da-da.

How wonderful would it be to forget everything? Forget that the mornings did not bring with them the promise of excitement, but just another day. Forget that the evenings did not bring with them the anticipation of adventure, but just darkness. Forget it all and start fresh, start over.

The meadowlark was walking along the ledge of the birdbath, interrupting the stagnant water this time with its feet instead of its beak, looking just as impatient as it did wise. You can never start over. The new life you may create is filled with memories of the old one. The new person you may become retains the essence of who you were.

No, Michael thought, I want to escape all this. I want to escape who I am!

Humans, such a foolish species, the lark thought. Da-da-DAH-da da-da-da. You can never escape your true self and you’ll never be able to escape this world until you accept that.

Michael watched the meadowlark fly away, perhaps with a destination in mind, perhaps just willing to follow the current—regardless, out of view, gone. And Michael remained. The water in the birdbath still rippled with the lark’s memory, retaining what was once there, proof that there had been a visitor. Michael wondered if he would leave behind any proof that he was here when he left, if he ever left. Not that he cared if anyone remembered his presence, but simply to leave behind proof that he had existed before he began to live.

He turned his back to the window, the meadowlark’s memory and song, the flooded earth—none of that truly belonged to him anyway—and he gazed upon his room. For now, this sanctuary was all he had. He was grateful for it, grateful to have some place to wait until the waters receded and his path could lead him away from here.

But that would not happen today. Today his world, as wrong as it was, would have to do.

chapter 1

Before the Beginning

Like a snake slithering out of the brush, a bead of sweat emerged from his wavy, unkempt brown hair. Alone, but determined, it slowly slid down the right side of his forehead, less than an inch from his hazel-colored eye, then gaining momentum, it glided over his sharp, tanned cheekbone. Now the bead grew into a streak, a line of perspiration, half the length of his face. He turned his head faintly to the left and the streak picked up more speed and raced toward his mouth, zigzagging slightly but effortlessly as it traveled over the stubble on his cheek and stopping only when it landed at the corner of his mouth. He didn’t move. The streak grew into a bubble, a mixture of water and salt, and hung there nestled between his lips until his tongue, in one quick, fluid movement, flicked it away. Then it was gone. All that remained as proof that it had once existed was the wet stain of perspiration that ran from his forehead to his mouth. That and Michael’s memory.

Sitting next to his grandpa in the front seat of his beat-up ’98 Ford Ranger, Michael had been watching R.J. in the rearview mirror as he pumped gas. He was still watching him, actually; he couldn’t help it. His viewing choices were his grandpa’s unwelcoming face, the flat dirt road, the dilapidated Highway 50 gas station, the cloudless blue sky, or R.J. Without hesitation, his eyes had found the gas station attendant, as they always did when he accompanied his grandpa on Saturday mornings to fill up the tank on their way to the recycling center. Today, the last Saturday morning in August and a particularly hot one, found R.J. more languid than usual.

He pressed his lean body against the Ranger, his left arm raised overhead and resting on the side of the truck so that if Michael inched forward a bit in his seat, he could see the hairs of R.J.’s armpits jutting out from underneath his loose, well-worn T-shirt. Michael inhaled deeply, the smell of gasoline filling him, and his eyes followed that smell to the pump that R.J. held in his right hand. Michael’s eyes moved from the pump to R.J.’s long index finger wrapped around the pump’s trigger and then traveled along the vein that lay just underneath R.J.’s skin. The vein, large and pronounced, started at his knuckle, spread to his wrist, and then moved along the length of his arm until it ended at the crease of his elbow. His arm, flexed as he pumped the gas, looked strong, and Michael wondered what it would feel like. Would it feel like his own arm or like something completely different? Something much better.

Absentmindedly, Michael touched his forearm; it was smooth and hot. He traced his own much smaller vein with his finger and he could feel his pulse, rapid, restless, new, and he wondered if beneath R.J.’s lazy demeanor his pulse was just as quick. Or was Michael the only one who felt speed underneath his skin?

The click of the gas pump ended all speculation. Michael shot a quick glanc

e to his grandpa, who was staring out at the land, busy smoking his third Camel in an hour, since his grandmother refused to allow him to smoke inside the house. As always his mind, like Michael’s, was elsewhere.

Michael heard the snap as R.J. returned the nozzle to its cradle, the quick tick-tick-tick as he closed the gas cap, and the slam as he shut the cover of the gas lid. And just as he turned to look out his window, hoping to catch a whiff of R.J.’s scent as he walked around the car to collect the cash from his grandpa like he always did, R.J. decided to change the rules. He squatted down next to Michael’s window and peered into the truck.

“That’ll be twenty-seven fifty,” R.J. said in his usual low hum.

This was a surprise. Underneath his skin he felt his pulse increase, but Michael had learned not to show the outside world what was happening inside him and so his expression remained calm. Just another bored teenager sitting in a truck with his grandpa on a hot August Saturday morning. But he was much more than bored; R.J.’s face ignited curiosity.

Unable to turn away, Michael soaked it all in. Up close, Michael could see that there were a few more beads of sweat on R.J.’s forehead, lingering there, not yet ready to take the trip down his face. While Michael’s grandpa reached into his front pocket to pull out his cash, R.J. rested his chin on his forearm and closed his eyes. His eyelashes were like a girl’s, long, delicate, with a beautiful upcurl to them. Michael had the urge to run his finger through them as if they were strings of a harp. Like most of his urges, he repressed it.

How many freckles were on his slender nose? Six, eight … before Michael could finish counting, R.J. brushed his cheek against his arm, wiping away any telltale signs of perspiration that had remained, and looked up directly into Michael’s eyes. His mouth formed a smile and then words, “Hot today, ain’t it?”

Keep looking bored, Michael thought, uninterested, so no one will suspect. “Yeah,” Michael said, nodding his head.

“Gonna be a scorcher today,” Michael’s grandpa said, “but ya can’t trust those weathermen to know nothin’.”

R.J.’s face retained its expression, no change whatsoever. Was R.J. suppressing what he really felt too, or did he agree with Michael’s grandpa? “Can’t really trust anybody,” R.J. said. “Can ya, Mike?”

That sounded odd to Michael’s ears; nobody called him Mike. He wasn’t a Mike, it didn’t fit, but maybe it could be the name that only R.J. used. That would be okay. Michael cleared his throat and then replied, “Guess not.”

“Here.” Michael’s grandpa thrust some bills in front of Michael, and R.J. reached out to grab them. A beat later, Michael reached forward to grab the money and pass it along to R.J., but he was too late. Or maybe he was right on time? His fingers brushed against R.J.’s forearm and he discovered that R.J.’s skin was just as smooth as his, but much hotter and firmer than his own. Michael mumbled “sorry,” but he was drowned out by his grandpa’s command, “That’s twenty-eight there, Rudolph; credit me fifty cents next time.”

Rudolph. Michael’s grandpa was the only one who called him by his real name. Sounded more inappropriate than calling Michael Mike. But Mike and Rudolph? That had an exciting sound to it. Michael didn’t see R.J.’s patronizing smile; he kept his gaze down at the fingers that had recently touched his skin, but he did hear him. “Will do, sir.” He didn’t look back up until he heard the motor running and heard his grandpa shift the car into drive. He turned to catch one more glimpse of R.J.’s face, but he had stood up and all Michael could see was his hand stuffing the cash into the frayed pocket of his jeans. And then there was a breeze.

R.J.’s T-shirt lifted and for a moment his hip flank, sharply defined and smooth, was exposed. Michael thought it looked like a small hill on an otherwise flat plain where he could rest his head, maybe dream a little. As the truck pulled away, Michael looked through the rearview mirror, but the breeze had died and R.J.’s T-shirt covered that interesting piece of flesh. Later that night, Michael would remember it, though, because no matter how hard he tried, he just knew it was something he wouldn’t be able to forget.

After Michael helped his grandpa bring the cans and bottles to the recycling center, there were other errands to run. Had to pick up a new fog light at Sears that he would later be forced to watch his grandpa install in his mother’s car because she turned a corner too sharply and busted hers; then they had to drive over to the Home Depot to get a new toilet chain that Grandpa would watch Michael install in the downstairs bathroom; and of course it wouldn’t be Saturday if his grandpa didn’t play the Nebraska Lottery.

“Up to a hundred seventy million this week,” the redheaded cashier informed them.

“If I win, you and me’ll bust outta here,” Grandpa said.

“My bags are already packed!” the redheaded cashier chortled. Even though the cashier was roughly forty years younger than his grandpa and still what locals would call fine-lookin’, Michael had no doubt that if his grandpa came back next week waving a winning lottery ticket, she would hop in the Ranger to drive off with him to parts unknown. Weeping Water was not the kind of town that instilled loyalty in its residents, unless they had nowhere else to go.

But Michael did have some place he could go. He had started his life somewhere else, he was born someplace far, far from this town, where he could be living right now. But his mother had put an end to all of that. Why?! Why had she ruined everything? No. No sense blaming her now; the damage had already been done. He would just spend the rest of the day imagining how far from here he would travel if he were lucky enough to win the lottery.

When all the dinner dishes were washed and put away and his grandparents were sitting in their own separate chairs in front of the television, he finishing an after-dinner beer, she finishing yet another knitting project, Michael sat on his bed rereading A Separate Peace, one of his favorite novels, some music that he vaguely recognized filling the space of his room. Before he finished chapter one, his mother knocked on his door to ask the same question she’d been asking all summer long.

“Heya, honey, aren’t ya going out tonight?”

Grace Howard had once been a beautiful woman. So beautiful that she won a series of beauty pageants culminating in Miss Nebraska, which meant that she could fly to Atlantic City to participate in the Miss America contest. Pretty big stuff for any town desperate for some notoriety, incredibly huge stuff for a town like Weeping Water. She didn’t crack the top ten, but she did catch the eye of a young college student on vacation from England. Against the vehement protests of her parents, Grace nixed a return to Nebraska and instead flew to England with Vaughan. She had never done anything so spontaneous or rebellious in her entire life. Three months after the contest, she and Vaughan Howard got married on his family’s estate in Canterbury, roughly an hour southeast of London. Vaughan was her winning lottery ticket. Until she decided to rip it up into little pieces and return home, dragging her crying toddler with her.

“No, I need to finish this before school on Monday,” Michael lied with just a glance in his mother’s direction.

“But it’s the last weekend before school starts back up.”

Don’t remind me, Michael thought. “I know, that’s why I have to finish.”

His mother was in his room now, which meant that either she wanted to discuss something or she was incredibly bored and had exhausted all conversation with her parents. “Can’t believe you’re a sophomore already; my little guy’s gettin’ to be a man.” She was standing in front of the oak bookshelf, looking at the spines of all the books Michael had read and would most likely read again. They were his escape. It didn’t take a genius to figure that out. “I hated to read when I was your age; still can’t concentrate long enough to get through a magazine article.”

From behind, Michael’s mother still looked youthful. Her brown hair was full and fell an inch or two below her shoulders, her arms were taut and hadn’t yet gotten flabby, and her hips still held their curve. It’s when she turned to

face Michael that he saw age had crept into her face prematurely. Michael knew that a thirty-seven-year-old woman shouldn’t look like that.

“You know Darlene’s daughter?”

“Who?”

“Darlene Garrison. Michael, sometimes …” Now she was fiddling with something on his desk. “Sometimes I don’t think you pay attention to anything except these books of yours. Darlene owns the beauty parlor A Cut Above; she does my hair. Her daughter, Jeralyn, is in your grade.”

Michael had no idea who Jeralyn Garrison was, so he lied again. “Oh yeah, I think so.”

“Where’d you get this?” His mother held up a Union Jack bumper sticker.

“I found it at the Sears auto store when I was there with Grandpa. He told me I couldn’t put the British flag on his Ranger. I told him I had no intention of doing that; I bought it ’cause I liked it.”

Michael saw the familiar glaze come over his mother’s eyes. He remained silent because he knew that if he kept on talking, if he asked her a direct question even, she wouldn’t hear him. She was in the room, but her mind wasn’t. Her heart might not be in the room either, but his mother rarely talked about what lay in her heart, so it was hard to tell about that. When she placed the bumper sticker gently back on his desk and turned to face him, he was compelled to speak despite knowing it might be futile.

“Do you ever miss London?”

Grace looked at her son. He doesn’t look a thing like me, does he? I don’t have blond hair, my skin isn’t so pale, my eyes aren’t green. If I hadn’t been there when the doctor pulled him out from inside of me, I would never believe this person was my flesh and blood. But he was, he is, she thought. In some ways, he’s all I’ll ever be able to truly call my own.

“No,” she lied. “I told you before, it’s a crowded, loud city. Dirty, no space to breathe, no clean air. I can’t believe you remember it; you were only three when we left.”

Unwelcome aa-2

Unwelcome aa-2 Moonglow

Moonglow Unafraid aa-3

Unafraid aa-3 Sunblind

Sunblind Starfall

Starfall Unnatural

Unnatural Unafraid

Unafraid Unwelcome

Unwelcome Unnatural aa-1

Unnatural aa-1