- Home

- Michael Griffo

Moonglow Page 14

Moonglow Read online

Page 14

Dutifully, Barnaby and I played along. And if it hadn’t been for my father’s last comment to me before he drove off with Jess’s body wrapped in a dingy blanket in the trunk of his police car, I would have thought he was just doing his fatherly duty: protecting his daughter. But his words make me think that he’s also protecting himself.

This is all my fault.

That’s what he said. He didn’t explain what he meant; he didn’t elaborate on his comment. He just drove off and ignored it when he returned home. As confused as I am about my father’s motives, I want to protect him as much as he’s protecting me, so when Danny Klausman asks if I heard from Jess, I do as my father taught me. I lie.

“She sent me a bunch of birthday texts,” I say as casually as if I were telling the truth. “I had to cancel my dinner ’cause I must’ve caught a stomach bug or something; my brother had it too.”

I prove to be a good liar, and Danny believes every fictitious word I’ve told him.

“Could’ve been food poisoning,” he suggests. “I had that once when my mother tried to make Mexican. Her chili was rancid or something. The whole family was going from both ends if you know what I mean.”

Sadly, I got the picture. Danny really is disgusting though, and for once I don’t feel bad for dubbing him The Dandruff King.

“Did that happen to you?” he asks with an expression that can only mean he’s hoping my answer is yes.

“Just throwing up,” I say. “But Barnaby wasn’t, so I don’t think it was anything we ate, just a dumb virus.”

It is so easy to lie. I never really did it before, never saw the point to it unless, of course, it was a way not to hurt someone. But it’s also hard to keep a lie straight. Now that I’ve mentioned that Barnaby didn’t throw up, made that part of our fake scenario, I have to make sure that’s what he tells people or I’ll be proven a liar. And if I can lie so effortlessly, chances are an eager assistant D.A. will make the case that I can commit murder with the same ease. Now I know why I rarely lie; it’s hard work. I have never been more thankful to see Mrs. Gallagher walk into class, because for the first time in my life geometry doesn’t seem so complicated.

Getting through lunch, however, is going to be like getting through one of those laboratory mazes. I’m a mouse in search of a piece of cheese, and I simply don’t know which way to turn to find my reward.

“Domgirl! I can’t believe you were sick on your birthday,” Caleb declares.

Do I turn to the left or to the right? Do I stand still? Do I let the guilt that’s clawing at my insides break through my skin and confess, or do I maintain my made-up innocence?

“Total bummer,” I tell him sheepishly. Fake innocence wins.

“So what up?” he asks. “You were feeling okay when I saw you during last period. Something happen after school?”

An inner voice tells me that “Lying is another word for protecting.” It’s exactly the reminder I need to get me to open my mouth and speak.

“No, I wasn’t feeling great all day, but I thought it would pass,” I say. “It did, but only a day later.”

“Well, this weekend we’ll do something,” Caleb says. “Just me and you.”

Smiles are contagious, and in spite of what I’m hiding in my heart, I look harmless, one half of a smiling couple. I’m just a girlfriend enjoying a sort-of-intimate moment with her boyfriend at a lunch table in the middle of a normal school day. Like a bad omen the scratches on my chest tingle; I’m about to discover this is a day that’s about to become anything but normal.

“Ohmigod, ohmigod, ohmigod!” Arla whisper-shouts as she sits at our table in an empty chair next to Caleb and across from me. Not quite sitting actually; her leg is tucked under her so she’s sitting on her calf, and her body is leaning across the table. She’s acting like one of those special ADD students whose parents are unsuccessfully trying to wean them off of Ritalin. Her body is bouncing slightly, so her long crystal necklace isn’t just dangling from her neck; it’s swaying, the crucifix at the end of the necklace swinging toward me, then retreating as if salvation were just out of my grasp.

“Did you hear about Jess?”

Her hand feels warm on top of mine. I look down, and I have to fight back the tears. Don’t give yourself away; don’t give them any reason to question you later; keep lying; keep acting as if you don’t know anything. That’s what I tell myself, but it’s hard when I see Arla’s hand, because it reminds me of Jess.

Not in the color or texture, but in the fingernails. They’re painted Jess’s favorite color, lemon yellow. The MAC name for it is Sunblind, and the shape is the squoval that Jess just introduced us to. Only last week we piled on her bed to rewatch—for about the fifteenth time—the online video starring Saoirse demonstrating how to achieve the square-meets-oval look on her friend Nakano’s hand. Jess so adored Nakano that she e-mailed him to tell him he should branch out and do his own spinoff videos. He wrote her back and thanked her, but said he’s happy just being Saoirse’s sidekick.

I’m so lost in absurd thoughts about Arla’s fingernails and Jess’s online friends that I see Arla’s mouth moving, but I don’t hear what she’s saying.

“Rewind please?” I ask.

She runs a squovalized fingernail through the bangs of her wig. Since it’s Thursday, she’s sporting her goth-black, shoulder-length, straight-haired wig with bangs that tickle the tops of her eyebrows. It’s Jess’s favorite for the obvious racial implications. Just as Arla shifts in her chair and lets go of my hand, I start to shake. I can’t help it; all I’m doing is thinking about Jess, seeing her face in front of me, the “before” and the “after” looks, and now I have to listen to Arla talk about her.

“My father told me that Jess disappeared,” Arla repeats.

“What?!” I say. It’s only one word, but I say it with such conviction that I hate myself.

“Like vanished?” Caleb asks.

“Poof,” Arla replies, snapping her fingers. “Into thin air.”

“Oh come on,” Caleb says, shrugging his shoulders. “That’s ridiculous.”

“Tell that to her mother,” Arla replies. “She never came home after school and that was two days ago!”

Words and ideas are forming in Caleb’s mind; he’s trying to digest this information and make it palatable. He’s got innocence and an optimistic spirit on his side, so he should be successful. He is.

“She’s probably being all dramatic about something stupid and took off. They’ll find her,” Caleb says confidently. “She can’t be that far, and nothing ever happens in this town anyway.”

Cupping her chin with her hand, Arla presses one lemony-yellow squoval-shaped fingernail against the side of her light brown cheek. The color combination is like something out of a design magazine. Her words, however, are right out of the police blotter.

“Remember Mauro Dorigo?”

“Who?” we both ask.

“Fat bully a few years ahead of us,” she clarifies. “About two years ago he up and disappeared right around Thanksgiving too.”

Recognition seeps into Caleb’s face, but not into mine. Clearly, Arla is much more informed as the daughter of the deputy sheriff than I am as the daughter of the man in charge.

“Whoa! I do remember hearing about that,” he exclaims. “He was a runaway right?”

Arla’s eyebrows rise so high they get lost amid her bangs. “That’s what they told the press,” she explains, knowing full well that we know “they” means “her father.” She drops her chin and her voice. “But there was no note, no family problems, nothing that would indicate he’d want to run away,” she confides. “And there hasn’t been a trace of him ever since.”

I have to ask. “So your father doesn’t think Jess ran away either?”

She grabs my hand again, but by now I’m so cold she can’t warm me up. “Oh, Dom, I’m sorry, I thought your father would’ve told you already.”

I can only shake my head.

“Should�

��ve known,” Arla replies. “Your father’s professional; mine’s got a big mouth.” She waves her hands to make us lean in closer to her so she can finish her story. “They don’t know anything yet, but my father said the first twenty-four hours, which we’re already passed, are the most crucial and so far they don’t have a clue.”

“What about Napoleon?”

I try not to look as shocked as Arla and Caleb when I ask the question. My goal is to make my face look like I’ve made a valid deduction, not like I’m casting blame on someone else. “I mean, you know,” I stutter, “he is her boyfriend; maybe she’s with him.”

“They’ve already talked to him,” Arla says, shaking her head. “Anyway, Dom, you know that Nap would rather be with you than with Jess.”

Even if I didn’t agree with her, even if I were the Helen Keller of Two W, I’d still have to protest. Remember, I’m sitting across from my boyfriend. The same boyfriend I’ve been trying to convince that he has no rival.

“Oh that’s ridiculous!”

“Dominy Suzette Robineau! You cannot tell me that you haven’t noticed the way that boy looks at you?” Arla asks.

“And just how does that boy look at my girlfriend?”

“Nap looks at Dom the way he should be looking at Jess,” Arla replies.

“I knew it!” Caleb explodes. “I’ve had just about enough of this d-bag!” Caleb stands up, and his eyes scour the cafeteria in pursuit of his nemesis. I look at Arla with a scrunched up expression that silently asks, “Why’d you have to spill the beans?” And she responds with an equally scrunched up expression that silently says, “I’m sorry; I thought he already knew.”

“Where is he?” Caleb asks, his neck twisting side to side. “It’s time I taught twinboy a lesson in how to behave.”

Arla and I twist our necks as well, hoping to find Napoleon before Caleb does in order to prevent the inevitable fistfight.

I search for the sweetest, most girlfriendy voice that I possess. I find it. “C’mon, Caleb, forget about Napoleon,” I practically purr.

“Not until he understands the rules,” Caleb seethes. “You’re my girl, so hands off!”

“Caleb,” I say in that same sugary voice, “he never put his hands on me.” I’m hoping this piece of information will placate him, make him stop acting like a Neanderthal. It has the opposite reaction, even though his vocabulary expands by a few centuries.

“I’m speaking figuratively!” he shouts.

The only thing that prevents Caleb from leaving the table to search for Nap in every classroom throughout Two W is Archie’s arrival. I can sense that something’s wrong while Archie’s still two tables away. Gone is his bouncy walk, gone is his trademark smile, and when he sits down next to me there’s no funny greeting, no fist bumping with Caleb, just a dour expression and silence. His gaze is unfocused; he’s staring at something on the table, and he wears sadness as if it were a perfectly tailored jacket.

I’m not sure if it’s biologically possible, but he looks whiter than usual; in fact, the only color in his face is coming from his eyes. Spreading out from the outer rim of his deep purple irises, a common albino trait, are spindly red spider webs, so numerous and thick that they threaten to wipe out the white parts of his eyes. Archie’s been crying, and he looks as if he’s about to start all over again.

“Winter, what’s wrong?” Caleb asks.

Slowly Archie looks up at us. He wants to speak but has lost the ability.

“Dude, tell us,” Caleb says kindly. “What’s going on?”

When he speaks, his voice is hoarse and shaky. “They found Jess.”

This is what it must feel like for people who are about to hear a jury’s decision or the results of a biopsy; they exist in a kind of suspended animation. Not breathing, not really living, just waiting for a signal from some more intelligent, exterior force as to how they should react. Should I sigh in relief? Should I squeak in delight? Or should I remain quiet and ponder how I’m going to die?

If they have found Jess’s body, it’s only a matter of time before they connect her death to my father or me; either way the truth will be revealed, and I’ll have to pay for my crime. Doesn’t matter that I can’t remember committing any crime, that I had absolutely no motive; I’m still going to have to pay. And the three people sitting at the table with me will want to see that happen.

“Why don’t you sound happy about that?” Arla asks nervously.

Archie’s focus returns to the table. “Because . . .”

When it’s obvious Archie can’t find the right words to continue speaking, Caleb interrupts him. “Because what?”

“Because they only found part of her.”

The significance of that statement doesn’t penetrate right away. Part of her. What’s he talking about? That phrase doesn’t make sense. Until Archie takes his iPhone that he’s been clutching and places it on the table so we can read the news bulletin on the screen.

A girl’s right arm has been found in the brush near the hills in Weeping Water; it looks to have been bitten off by a wild animal. The only identifying mark is a bracelet the victim was wearing spelling out her name—Jessalynn.

“The gift Napoleon gave her,” Arla says out loud.

Archie nods his head, and it’s like a domino effect. It starts slowly; first Arla reacts and then Caleb and then one person after another after another in the cafeteria starts to scream. Screams mixed with words. One word, actually, as Jess’s name echoes throughout the cafeteria, jumping from one table to the next. Obviously Archie isn’t the only one to have uncovered this news, and anguished voices fill the lunchroom, mine among them. The only difference between me and everyone else is that they’re screaming for their friend; I’m screaming for myself.

Within seconds our principal’s voice comes over the loudspeaker, instructing the students and faculty to report to the gym immediately for an assembly. I watch the crowd start to move in clusters, slowly, bodies hugging awkwardly, arms wrapped around shoulders, foreheads pressed together, and I wish I were blind. I hear the choked sobs, the wailing cries of disbelief from the students, and the stern, solemn orders from the faculty to keep moving, and I wish I were deaf. I feel Caleb and Archie and Arla grab me, hold me, clutch me close to them so our individual grief can fuse together to become one giant broken heart, and I wish I were invisible. I can’t be a part of this charade. My father was wrong. This isn’t because of him; this is because of me. I’m the cause of everyone’s pain; I’m the cause of everyone’s sorrow, so I can’t be a mourner as well.

I’m not proud of what I do, but I use Caleb’s jealousy of Napoleon to ensure my freedom. I see Nap enter the cafeteria, like a salmon swimming against the tide, and when he’s a few feet away, he stops to stare at me as usual. This time, however, I maintain his gaze. The tears I’ve been holding back are given their independence, and they stream down my face. As expected, Napoleon is at my side in seconds, his thin arms around me, his hands stroking my shoulders, brushing my hair off my wet cheeks, to comfort me in my time of grief. He really does feel like a butterfly, soft, wispy, and unable to keep still. A few seconds after his butterfly-touch, and Caleb is pushing Napoleon off of me, shouting, “Keep your hands off my girlfriend!” Boys really can be so predictable.

During their scuffle, I back away, and without worrying if anyone sees me, I run out of the cafeteria in the opposite direction from where the crowd is heading. I have no choice. There is absolutely no way I’m going to be able to sit in the bleachers surrounded by my shell-shocked classmates and listen to Dumbleavy and his team of lame counselors guide us through the labyrinth of our difficult-to-navigate emotions. The best way I know how to deal with these feelings that are eating away at me is to talk to someone who can’t talk back.

For once Essie’s poor job skills are to my benefit. She doesn’t ask me why I’m visiting The Retreat during school hours; she merely hands me an index card with the number nineteen written on it in black Magic Marker. Tod

ay’s index card color is orange, so I’m reminded of Halloween, which I think is highly appropriate since I’m masquerading as the heartbroken, innocent best friend. Well, two out of three adjectives isn’t bad.

Inside my mother’s room I can let the mask fall; I can be myself, whoever that person really is. I follow my usual routine so I can relax. Pull the chair next to my mother’s bed, sit down, repeat my opening line: “Hey, Mom, how are you?” There’s no response, which I’ve come to expect, but there’s no calmness either, which I’ve come to rely upon. I take a deep breath to slow down my racing heartbeat, and when I exhale for the third time I realize the problem: I’ve forgotten her perfume.

Instead of filling up with lilacs and powder, the scent of her favorite Guerlinade, my lungs fill up with antiseptic and some other heavy scent that I don’t recognize. Must be some cheap perfume from a nurse or maybe a housekeeper, not sure, but definitely from someone who can’t handle the smell of sickness all day long so she bathes in some musky cologne. I hate the smell, but I can’t blame her; it’s no different from what I do.

I grab my mother’s hand, and thankfully it’s as smooth as ever; it’s good to know some things don’t change. The back of her hand feels so warm against my cheek, it’s like I’m sitting in front of a roaring fire. I close my eyes, and I can see the flames dancing, orange, red, and yellow pieces of fire interwoven, leaning and bending, destroying all that’s bad, all that needs to disappear, and leaving behind only remnants of sorrow, so it’s easier to move forward; it’s easier to keep on living. That’s what my mother shares with me, the ability to move on. In the crackling of the flames I can hear her voice, the voice that I remember, the voice that reminds me I can share anything with her and she’ll love me unconditionally and she’ll always be able to make my world perfect again. The sound is like a lullaby, crackling and hissing and squeaking. Squeaking?

Unwelcome aa-2

Unwelcome aa-2 Moonglow

Moonglow Unafraid aa-3

Unafraid aa-3 Sunblind

Sunblind Starfall

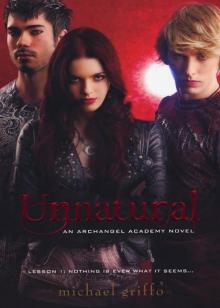

Starfall Unnatural

Unnatural Unafraid

Unafraid Unwelcome

Unwelcome Unnatural aa-1

Unnatural aa-1